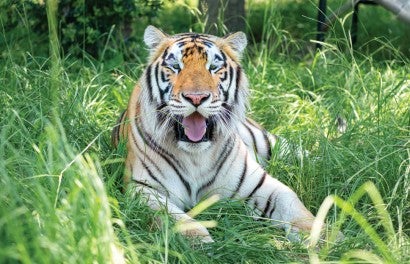

India leaps into his pool, pouncing on a purple plastic egg—his favorite toy, according to his caregivers. After a few minutes, the tiger ambles over to his watering tub. Instead of taking a drink, he plops in and closes his eyes in contentment. Although he’s young—roughly 10 months old on this June day—the massive paws hanging over his tub are a reminder of how strong he already is and how much larger he will become.

With room to roam and places to swim, India has lived a dramatically different life over the past few months than the one he used to know. Before his May arrival at the Humane Society of the United States’ Black Beauty Ranch in Murchison, Texas, India was kept as a pet in a private home. Many details of his prior life are unknown, but videos of people bottle-feeding him and the bejeweled collar he wore when he was rescued indicate how different his life was from that of wild tigers—and his life at the sanctuary.

Countless tigers like India live in roadside zoos, circuses, and private homes across the country. No one knows exactly how many captive tigers there are in America, as no federal agency keeps track of these animals. The vast majority of these tigers spend their lives in cruel conditions where they cannot express their natural behaviors. Although private owners and roadside zoos may claim their captive tigers help conservation efforts, these animals are usually habituated to humans and unlikely to survive if ever released into the wild. Many tigers are crossbred between subspecies who would not interbreed in the wild.

They’re adorable when they are young, but they’re wild animals. They don’t belong in the public’s hands.

Noelle Almrud, Black Beauty Ranch

In March 2020, the captive tiger problem gained mainstream attention with the Netflix series Tiger King, which followed the antics of U.S. roadside zoo operators. As the show’s human stars gained notoriety due to their eccentric personalities, animal advocates warned that the series glossed over the abuse endured by the big cats at these zoos.

More than a year later, many of the operators featured in Tiger King are now facing legal troubles for mistreating their animals, and viewers of the series are seeing the dark side of private tiger ownership: So far in 2021, authorities have seized three pet tigers from Texas neighborhoods.

Among them was India, rescued by authorities in May after a viral video showed the tiger wandering the streets of Houston. Just a few months earlier, Elsa was seized by the Bexar County Sheriff’s Office after deputies responded to a call about a crying animal and found the 6-month-old tiger living in an outdoor cage in freezing temperatures. She was wearing a harness and had rubbed her forehead raw on the bars. Elsa also found a permanent home at Black Beauty Ranch (“A home for Elsa,” Summer 2021).

With the two newcomers, the sanctuary is now home to three tigers rescued from the pet trade. Loki arrived first, in February 2019, after being found in an abandoned Houston home, living in a cage so small he could barely move (“The tiger next door,” September/October 2019).

Tigers rescued from the pet trade often suffer health issues such as malnourishment and metabolic bone disease, say sanctuary staff. Owners generally buy food that is inexpensive and easily accessible—such as meat from chickens or domestic cat food—but lacks essential nutrients. At the sanctuary, the young tigers—India and Elsa—are fed twice daily to help them grow. When they reach adulthood, they will eat almost 3,000 pounds of food a year on a schedule modeled after wild tigers’ dietary behaviors.

In the wild, tigers roam expansive ranges. As pets, tigers are crammed into homes, forced to engage in unnatural behaviors such as cuddling with humans and walking on a leash.

“When people own them, they’re interacting with them all the time and they want them to essentially be a dog for them, and that’s just never going to work out,” Myers says.

Tim Harrison, director of Outreach for Animals in Ohio and a former public safety officer, has assisted in rescuing, relocating and providing care for over 1,000 big cats kept as pets. He says most people get a tiger without thinking through the long-term care the animal will need. “Everybody wants a tiger cub, but nobody wants a tiger,” Harrison says. Many tigers end up in cages when they grow older and more dangerous.

When Loki first arrived at the sanctuary, he was skittish and timid, likely because he was kept in a cage with little stimulation. He was scared of sounds like the wind blowing and the rustling of leaves. He didn’t know how to climb and was afraid to go into his pool. Now, more than two years after his rescue, he has become a confident and independent tiger. The pool is one of his favorite spots and he can often be found lounging on his platform.

When India arrived at the sanctuary, he played in the grass and pool for over an hour straight, only stopping after he wore himself out.

“Once he got out into his yard, it’s like he realized, ‘this is what I was meant to do. This is what a tiger is meant to be,’ ” says Christi Gilbreth, senior animal caregiver at Black Beauty Ranch. In his expansive enclosure, India is strengthening his muscles and exploring natural tiger behaviors.

As pets, the tigers’ lives revolved around the desires of humans. At the sanctuary, humans cater to their species-specific needs—and individual personalities.

One way they do this is through the tigers’ enrichment. Loki enjoys playing with toys in his pool, so the caregivers set them up along his waterfall. Elsa and India have lots of youthful energy, and caregivers provide them with toys that move around and encourage play—including India’s purple plastic egg, which is lightweight enough for him to toss around but sturdy enough to withstand his pounces.

Caregivers monitor the tigers daily to ensure their physical and psychological needs are met. The tigers have multilevel platforms for exploring, pools for swimming and cooling down, and trees surrounded by long grass for stalking. Every week staff change out their toys to prevent boredom.

“While we’d love for them to be in the wild, we give them the next best thing,” says Gilbreth.

India, Elsa and Loki are the lucky ones. They have been rescued and live in sanctuary—but only because they lived in areas where it’s illegal to own tigers. “You don’t hear about the ones who are housed in most parts of Texas where it is completely legal to have them,” says Almrud.

Texas has no state law banning the private possession of tigers. The state requires owners to register their tigers, but many don’t. Some counties have enacted bans, but others have lax or no regulation. The HSUS tries every legislative session to pass a ban on the private possession of dangerous wild animals, like tigers, but despite bipartisan support from legislators, cities, law enforcement and the Texas Animal Control Association, the Texas legislature has failed to pass this vital legislation. Across the country, 35 states ban the private possession of big cats and the HSUS is working to pass state and local laws in areas where it is still allowed. There have been some wins; Nevada recently passed a ban on public contact with dangerous wild animals, such as tigers.

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe