Danielle Tepper had always loved dolphins. When she went on vacation to Hawai'i, she knew she had to see them firsthand. Tepper—now a senior editor at the Humane Society of the United States—wanted to do it ethically, so she avoided captive dolphin attractions. Instead, she booked an excursion to swim with wild spinner dolphins. It wasn’t until years later, while working at the HSUS and editing an action alert on spinner dolphin attractions, that she realized her experience was inhumane.

Tepper’s story is common: Many people are drawn to animal attractions out of a love for animals but end up inadvertently supporting cruelty. Even with good intentions, it’s difficult to tell an inhumane operation from an ethical one.

Inhumane animal attractions come in many forms and involve a plethora of species, from cub petting attractions to unethical safari operators who disturb wild animals. All too often, animals suffer physical and psychological distress for human entertainment.

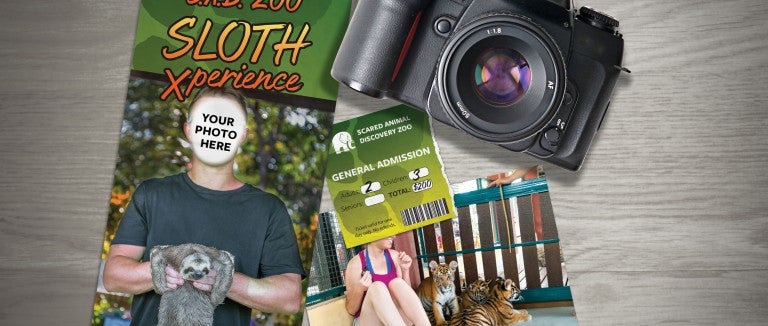

Travelers in the U.S. are most likely to encounter roadside zoos. Unlike facilities accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, roadside zoos are not required to abide by professionally accepted standards of care.

One notorious example is Natural Bridge Zoo in Virginia. A 2014 HSUS undercover investigation documented shocking abuses, including mother monkeys fiercely protecting their young as staff separated them, tiger cubs deprived of food so they would be hungry for bottle-feeding photo sessions and a pregnant giraffe who was found dead in her cage.

The HSUS provided evidence from the investigation to authorities. It wasn’t until nearly six years later that the U.S. Department of Agriculture fined the zoo just $41,500. The fine is substantial by USDA standards but is still not enough to deter cruelty, says Debbie Leahy, an HSUS senior strategist for captive wildlife.

Lack of enforcement and weak penalties are pervasive problems. Exploitative animal attractions can easily pay meager fines and continue business as usual. “The Animal Welfare Act is blatantly weak and vague, and the USDA is notoriously lax at enforcing it,” says Lisa Wathne, an HSUS senior strategist for captive wildlife.

It’s hidden from the public: the bad behaviors, the injuries and animals who are left lost and suffering in the back buildings.

Whitney Teamus, The HSUS

Inhumane attractions often deceive visitors into believing they are helping animals. They may market themselves as “sanctuaries” or “refuges” and tell the public they are contributing to conservation efforts by breeding endangered species. But animals bred in these facilities will never be released to the wild; they are bred solely for entertainment and profit, says Wathne.

Visitors “are blinded by being able to hold a baby tiger,” says Wathne. “It’s hard when you put animals in front of people for them to take in any other kind of information.”

Whitney Teamus, HSUS investigations manager, went undercover at Natural Bridge Zoo and saw the problems firsthand. But she does not blame visitors for wanting to interact with wild animals. “It’s not the public’s fault,” Teamus says. “It’s hidden from the public: the bad behaviors, the injuries and animals who are left lost and suffering in the back buildings.”

Travelers want that once-in-a-lifetime experience without feeling guilty. So it’s tempting to take facilities at their word when they say they are helping animals. But visitors need to conduct their own research before giving money to an animal attraction.

A simple rule is to avoid any place that offers direct interactions with wild animals. But beyond that principle is a lot of gray area. Even attractions that let tourists observe wild animals from a distance may cause suffering. Visitor overcrowding can harm animals’ physical and psychological health, in turn hurting their ability to protect themselves, reproduce and raise their young. The effects of human disturbance can be subtle and difficult for the average traveler to detect. And the public may observe wild animals grazing in open pastures at drive-through parks without realizing that many of these facilities sell surplus animals to hunting ranches.

While snorkeling with spinner dolphins, Tepper did not notice any red flags: The tour operator told snorkelers not to touch the dolphins, and the animals seemed unbothered by their presence.

If she hadn’t started a job in animal welfare, she might have never learned the truth. “You really need to scrutinize what you're doing to make sure it's as humane as you think it is,” says Tepper.

Spinner dolphins are nocturnal, feeding at night and resting in coves during the day. Since the dolphins keep half their brain “on” during the day, they still swim and come to the surface to breathe, and it’s not always obvious that they are resting. Some signs of stress—such as elevated heart rate and increased watchfulness—are not apparent to visitors, and other signs—such as leaping and spinning—might be misconstrued as playfulness. Stressed dolphins might even leave the safety of the cove, making them more susceptible to predators.

“You’re essentially going into their bedroom and saying, ‘entertain me,’ and it’s not respectful,” says Sharon Young, HSUS senior strategist for marine issues. “You’re asking the animal to behave in a way he would never behave normally.”

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe