Drive the narrow, winding road that leads north out of Murchison, Texas, and you pass pasture after fenced pasture grazed by cattle. Traditional ranches focused on the bottom line—what their animals can produce or be turned into. At last, around yet another bend, you see the oddballs who make the neighbors smile and shake their heads: bison, gone for two centuries in this region, once more feeding on East Texas grassland. A herd of fallow deer. A collection of horses who would instantly drop a conventional farm deep into the red.

Black Beauty Ranch was a childhood dream for Cleveland Amory, writer, humorist and founder of the Fund for Animals. It was also, maybe, his biggest jest. Here on prime cattle land—good grass and plenty of water—stretches a 1,434-acre “ranch” that is anything but.

Creatures who have suffered the greatest cruelties enjoy the greatest kindness. They will never be ridden or bred or displayed for money or hunted or eaten. It’s a promise the sanctuary has kept from its creation in 1979 through the Fund’s 2005 merger with the Humane Society of the United States, a pledge expressed in the last lines of Amory’s favorite book, Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty, posted at the sanctuary’s entrance. In the words of the novel’s equine protagonist, much used and abused:

I shall never be sold, and so I have nothing to fear; and here my story ends. My troubles are all over, and I am at home.

Black Beauty Ranch opened in a hurry on 83 acres to take in some of the 577 burros the Fund for Animals lifted out of the Grand Canyon by helicopter so the National Park Service wouldn’t shoot them as invasive pests. The sanctuary has grown to more than 800 animals of at least 40 species. Horses and burros make up more than half. The youngest and healthiest equines—some rescued from slaughter and federal holding pens, most from neglect—run in a herd of almost 300. During the winter, while pastures recover, they happily drift into groups to feed on 1,000-pound round bales of hay set out each day in a big field.

They are cared for not because of what they might do for people but because of what people have done to them. Take Tigger, a horse who’d been left unhandled and barely fed or given water. In 2015 he was seized from his West Virginia owner. He could not be trained to take a rider. But he’s accepted at Black Beauty Ranch, an emblem of the overbreeding that has left so many horses without proper care or at risk of being sold for slaughter.

Like the book for which it is named, written from a horse’s point of view, Black Beauty Ranch helps humans see the world through animal eyes. Each of the animals at the sanctuary carries a story. Together they tell a larger tale—of Amory’s activism, of the growth of the animal protection movement, of the work of the HSUS and the Fund for Animals, of landmark victories and fights still to be won.

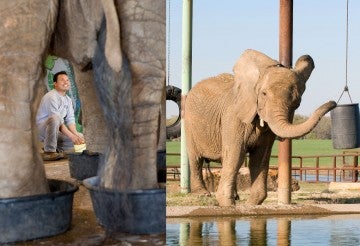

In the former elephant barn, now a hospital, a mural with an image of Babe, the ranch’s final elephant, greets visitors. As a 2-year-old in 1984, she watched her mother and aunts gunned down during a cull in South Africa’s Kruger National Park. Sold to a U.S. circus, she injured two of her legs while confined in a tight crate crossing the Atlantic.

In the circus, a larger bull elephant reinjured Babe’s rear right leg. She was lame when she reached the ranch in 1996. Her right rear leg would fail and she would lie down. After training her to lift her feet, caregiver Arturo Padron and other staff regularly trimmed her toenails, soaked her sensitive feet in Epsom salts and apple cider vinegar and carefully treated infections. She received a medication to dissolve calcium deposits, hydrotherapy in a pool and in a heated sandbox, relief from the pain in her legs. In 2010, in the midst of plans to transport her to an elephant sanctuary for companionship, Babe laid down one last time and did not get up. She was only a quarter century old—far short of the lifespan of a wild-living elephant.

Much of the cruelty that brought Babe to Black Beauty Ranch ended soon after. Culls no longer take place at Kruger—the HSUS and Humane Society International have pioneered a contraceptive that can humanely manage elephant populations. Following decades of criticism from the HSUS and other animal welfare groups, the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus stopped touring with elephants in 2016. The HSUS and HSI helped bring about an agreement under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) that greatly restricts the export of live, wild-caught elephants from southern Africa—a step toward the end of exports of elephants from Africa to the U.S. for entertainment.

“With cruelty and oppression, it is everybody’s business to interfere,” Sewell wrote in 1877 in Black Beauty. It was a radical idea at the time.

Noelle Almrud, executive director at Black Beauty Ranch, says she’s working for a world where animals no longer need sanctuary, where cruelty diminishes to the point that she’s out of a job. That chapter is yet to come.

Peanut

Gloucester pig

When the rescuers searched the broken-down farm in New York’s Hudson Valley, they encountered a horde of underfed, sick, parasite-ridden animals—calves with pink eye, sheep with protruding ribs hidden beneath shaggy maggot-infested wool, cows spooked because one of them had just been killed and butchered that morning. Then rescuers came to a dark barn where they found 14 hungry pigs and piglets, including a black and white 5-year-old male soon named Peanut, locked in lightless stalls, standing in wet manure. “We could hear their screams and they pushed at the doors to get out,” reported a rescuer. “Of all the animals we found, [the pigs] were the most psychologically damaged.” Peanut and five other pigs went to Black Beauty Ranch, where they got fresh straw to nest in, mud to wallow in, dirt to root in and days outdoors in sunlight.

At first, Peanut lacked confidence. Placed in a large group of pigs, he got picked on by the others. So ranch staff moved him to a smaller group. There Peanut found his place. In the morning, he and four other pigs come running to two troughs at the edge of a small pasture. At first Peanut hangs back, but eventually he pushes in to get grain, climbing into one trough, then the other, shoving a couple of pigs out of the way. Quickly and noisily, the pigs eat every last speck, sniffing for more. The grain is carefully measured so they don’t overeat and add extra pounds that take a toll on their joints. While Peanut was at the farm, his long-term health was unimportant. He would have soon been butchered. At Black Beauty Ranch, he eats for abundant life—many years, many naps in the straw, many belly rubs from caregiver Maura Flaherty, who scratches his coarse hair. “He’s super sweet,” she says. “He’s the chillest.”

I shall never be sold.

Big Red

European red deer

For years, Big Red lived with a price on his head, calculated according to the size of his antlers. Six points on each side made the European red deer a “management bull,” available to kill for around $3,500 at a Texas captive hunting resort. Big Red’s life would have ended with an arrow or a bullet, most likely without a chase. Then the hunter and the guide would have stood on either side of Big Red’s body and grasped his antlers, lifting his head for a photo. The HSUS and HSI oppose such canned hunting operations around the world. They number around 1,000 in the U.S., with an estimated 500 “exotic” animal ranches in Texas alone. Big Red was on his way to a trophy room wall when he, a younger male rival and a group of females were rescued in a seizure. Brought to Black Beauty Ranch, Big Red now presides over a harem of six females, while his rival, Spike, claims a group of female fallow deer (though both bucks are sterilized to prevent breeding). After living as a target for so long, Big Red sits far away from the fence that borders an expanse of grass and rocks and trees. But his magnificent antlers identify him. Once they were a prize for a hunter; now he uses them to playfully chase away Spike and impress the females. Big Red will probably live long enough that one day he’ll lose his harem to Spike. And that’s OK.

I have nothing to fear.

Bob

Wild horse

Bob was born in Nevada in a herd of wild horses on federal land where sagebrush, salt brush and cheatgrass grow. The Bureau of Land Management figures the 11,512-acre area can support about eight horses, but of course there are more. The HSUS has worked for decades to get the BLM to dart wild horses with a contraceptive called PZP to control their numbers, however the agency has yet to use the technology on a large scale. Instead, they round up horses, hoping people will adopt them. When Bob was about a year old, a helicopter appeared in the sky and drove his herd into a V-shaped chute that left them trapped. Bob was pushed into a metal box that held him for processing. He emerged, still wild, but with a freeze mark on his neck. Tens of thousands of gathered horses languish in long-term holding corrals. Bob was chosen for training and trucked to Kansas’s Hutchinson Correctional Facility, where minimum security prisoners gently work with horses, teaching them to trust people. In 2011, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection asked the prison for well-socialized horses for police to use at busy crossings with crowds and vehicles along the Rio Grande. They picked Bob because he was big. At his retirement in January, after seven years, Bob was the longest-serving Border Patrol horse. “Safe and dependable,” records say. When he was turned out into a Black Beauty Ranch pasture a little of the wild came back—he kicked up his heels and tore around the grass, whinnying. Now he’s meeting other horses one at a time, until he finds a friend and relearns the give and take of a group of horses, including kicks and biting. Then he can rejoin the herd.

Here my story ends.

Loki

Bengal tiger

Loki was left “temporarily” in a cramped makeshift cage inside the dark garage of a vacant Houston bungalow. He could only stand up, turn around and lie down and was living in his own waste, mixed with straw, trash, mold, maggots and rotting meat. Loki’s legs were raw and scalded with urine. After someone stumbled upon the 300-pound Bengal tiger while looking for a place to smoke marijuana, Loki’s owner, who had bottle-fed the big cat when he was a cub, was charged with animal cruelty and forced to give him up. The media treated the bizarre encounter as a kind of joke, but there are thousands of captive tigers in the U.S., maybe even more than the number still in the wild. Few get proper care. The HSUS has pushed for laws to stop people from displaying big cats in roadside zoos and traveling acts, charging visitors to feed, pet and pose with cubs and breeding, selling and keeping such animals as exotic pets. When Loki arrived at Black Beauty Ranch, he was friendly and curious, but timid, startled even by rustling leaves. As he began to explore his habitat, Loki walked gingerly on grass, as if it felt strange. Confined for so long in a 4-foot-high transport cage, he had to be coaxed inch by inch with treats to rise to his full height. “He had no idea that there was room for him to stand,” says caregiver Christi Gilbreth. It took Loki 45 minutes to follow a ball into a tub of water, but gradually he learned to enjoy his one-acre habitat, climbing up on a platform, sharpening his claws on trees and swimming in a pool and waterfall. When humans approach, the 2-year-old tiger pads over and greets them with chuffing sounds, rubbing against the chain-link fence to mark his territory. He playfully attacks a big blue rubber toy, grabbing it and biting it. Then he crouches, eyeing his next prey—a bear on one side of his habitat, a wildebeest on the other. Quite often, it’s Gilbreth. “He’s like a little kid,” she says. Life's a game.

My troubles are all over.

Nanette

Rhesus macaque

Nanette began life in a laboratory, one of roughly 110,000 monkeys in research facilities in the U.S. Some of the rhesus macaques in her lab were injected with hepatitis, some with HIV. The lucky ones were housed with a companion, living in rows of steel cages, trained with food to present their limbs for injections or blood draws or climb in a box to be taken away for an experiment. The luckiest were kept in breeding colonies with toys and branches to climb on, though babies were separated from their mothers days after birth. None went outside. The HSUS is pushing for the day when research and testing on primates, which causes physical and psychological pain, comes to an end. It’s important to remember, says Lori K. Sheeran, associate professor at Central Washington University, that macaques have the ability to worry. “One can only imagine the mental anguish these laboratory monkeys endure when a technician approaches, or when they see, hear or smell equipment used to intubate or otherwise harm them. They can mentally dwell on what torment the future will hold.”

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe