In 2019, Sara Shields, in southern India for workshops with Humane Society International colleagues, drove into the countryside near Bangalore to visit industrial chicken operations. At the first farm she stopped at, she saw hundreds of white-feathered birds in long open-sided barns with burlap curtains that could be lowered against the cold. Shields, HSI director of farm animal welfare, recognized the type. Tens of billions of chickens exactly like these are raised for meat worldwide. Called “broiler chickens” within the industry, they’re sold as chicks to farmers by just two companies that span the globe: U.S.-based Cobb-Vantress, owned by Tyson Foods, and German-based Aviagen. The chickens on the farm near Bangalore were most likely Cobb 400s, Indian-bred cousins of the Cobb 500, “the world’s most efficient broiler.”

These chickens have been bred to grow to market size in just six weeks. They have huge breasts, because, as Don Tyson said in the 1990s, “If breast meat is worth $2 a pound and dark meat is worth $1, which do you think I’d rather have?” But their explosive growth and oversize breasts pose risks, even to the bottom line—muscle abnormalities called “white striping” and “wooden breast” that show up in meat as tough areas of extra fat and collagen consumers don’t want. The cost to the chickens is far worse: pain; difficulty standing, getting up and walking; and reduced respiratory capacity. Every day producers walk through barns looking for collapsed chickens, says Shields. “It’s one of the main daily tasks: pick up the dead birds.”

On the Indian farm, although fans blew air to cool the birds, the tropical heat was taking a toll. Chickens were panting. The worried farmer confided to Shields that during an earlier heat wave he had lost almost a third of his 1,000 birds. “It’s unethical to breed birds like this” because they have exacting requirements that small producers in the developing world can’t always meet, says Shields. “Native chickens are adapted to the environment ... [Commercial chickens] are very, very sensitive.”

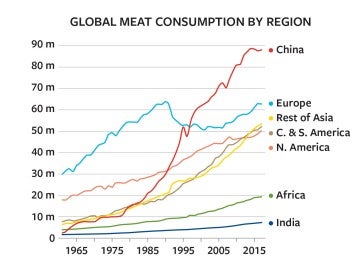

Though meat consumption is beginning to plateau in wealthy countries such as the U.S., it’s rising in most of the rest of the world. HSI wants to reverse that trend. It’s starting with a goal that food service providers, schools and other institutions can accept: reducing meat consumption by 20%.

“It’s very moderate, very easy—one day a week,” says Stefanie McNerney, HSI manager of global plant-based solutions. “Because it’s so minimal, they’re like, ‘OK, let’s try it.’”

Last fall, HSI/United Kingdom took the plant-based message to COP26, the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow. Scientists estimate that at least 16.5% of greenhouse gas emissions come from animal agriculture, including one-third of methane and nitrous oxide emissions, which trap up to 25 times as much heat as carbon dioxide. And though more than 80% of the world’s farmland is used for animal agriculture, that land produces less than 20% of the calories people consume, as crops are fed to 88 billion animals rather than directly to humans. Scientists say that to avoid catastrophic global warming people must eat less meat and dairy.

But lobbyists representing agricultural interests outnumbered animal welfare and conservation groups at COP26, says Stephanie Maw, a public affairs officer for HSI/UK who attended. While the event’s menu listed estimated carbon dioxide equivalent emissions for different dishes—3.3 kilograms for hamburgers versus 0.2 kilograms for plant-based burgers—livestock reduction and diet change weren’t on the main agenda. At a news conference, HSI called this omission “the cow in the room.”

“Animal agriculture is ignored at high-level conferences,” says Maw. “Why were they offering beef at a climate change conference? It’s like cigarettes being handed out at a lung cancer meeting.”

Are raised and slaughtered every year worldwide; commercial chickens have been bred to grow to market size in just six weeks.

Are emitted by producing a hamburger; a plant-based burger creates just .2 kilograms.

Could be offset by phasing out animal agriculture during the 21st century, which would also stabilize greenhouse gas levels for the next 30 years, according to a 2022 study.

Brazil is home to BRF, the world’s largest chicken exporter, and JBS, the largest meat processor. For many Brazilians, eating meat signifies status and Sunday beef barbecues represent the good life, say Thayana Oliveira and Anna Souza of HSI in Brazil. “My family would eat beef every day and chicken a couple of times a week,” says Souza.

Even in this meat-loving culture, HSI is reducing demand for factory-farmed products. The organization has helped introduce animal-friendly takes on familiar dishes in social assistance institutions for the elderly and children in the city of São Paulo (90 since 2018, for a total of more than 800,000 plant-based meals), and also in schools. School systems in five cities, including Jacareí, have reduced meat consumption by 40% (serving more than 3 million meals per year), despite a 2021 requirement by Brazil’s National Food Program that they serve meat four days a week.

“We know the importance of this project for the planet, for health and for the animals,” says Emily Bezerra Fernandes da Mota, nutritionist for the 90 schools in the Jacareí municipal system, which now serve almost a half a million plant-based meals a year: shepherd’s pie with textured soy protein, farro with soy and couscous, cookies with banana and oats. “If you introduce these recipes when [children] are young, they will build new habits for life.”

Trained by HSI, school chefs are already carrying recipes home. The hope is that the students will too.

In Viet Nam, HSI’s efforts to introduce plant-based dishes in schools and company canteens face challenges, says country director Phuong Tham. Until 1989, meat in the country was rationed and expensive. Now it is abundant: cheap chicken from Vietnamese factory farms and cheap pork imported from industrialized farms in Thailand. Parents—who pay for school meals—believe their children need to eat meat. Factory workers expect their employers to feed them meat, says Tham. HSI is educating people that plant-based meals can be just as filling and more nutritious.

In South Africa, HSI has won cage-free commitments from restaurant and hotel chains to reduce the number of hens confined in battery cages, says Leozette Roode of HSI/Africa. To reduce demand, HSI/Africa founded Green Monday, a program that promotes eating plant-based food and reducing meat consumption.

It’s bringing plant-based eating to the country’s urban townships, where the cheapest cuts of meat are sold—three or four chicken feet sell for the price of a banana—and where meat-based diets contribute to high cholesterol, high blood pressure and chronic illness. HSI organizes trainings with health experts and cooking demonstrations using local vegetables, grains and legumes; it also offers tips for growing tomatoes, potatoes, carrots, herbs and chilis in old tires, plastic containers and empty tins. Each participant is asked to share what they learn with 10 more people.

The trainings started in Cape Town. They will soon expand to Kwazulu Natal and Johannesburg. Ten times 10 times 10—a growing network of families cutting the demand that drives the global spread of factory farming. Bit by bit, inspired by HSI, they and others around the world are making small but powerful changes. Multiplied, their choices can spare the planet—and billions of animals’ lives.

HSI/Brazil created an e-book containing vegan versions of well-loved recipes. This recipe for feijoada—a savory black bean stew—comes from HSI/Brazil.

Want more content like this?

This was written and produced by the team behind All Animals, our award-winning magazine. Each issue is packed with inspiring stories about how we are changing the world for animals together.

Learn MoreSubscribe